With the growing popularity of Japanese tea ceremony, sadō (“The Way of Tea”), the accompanying traditional Japanese sweets, wagashi, are also increasingly enjoyed around the world. With delicate flavors, luminous colours and ethereal shapes, wagashi glisten on the plate like a whimsical treat. Intricately tied to the seasons, different wagashi accompany different months and seasons in order for a tea ceremony to be truly complete. Indeed, meticulous attention to detail is the true essence of Wabi-sabi, the rustic Japanese aesthetic of the impermanent, imperfect and incomplete nature of everything.

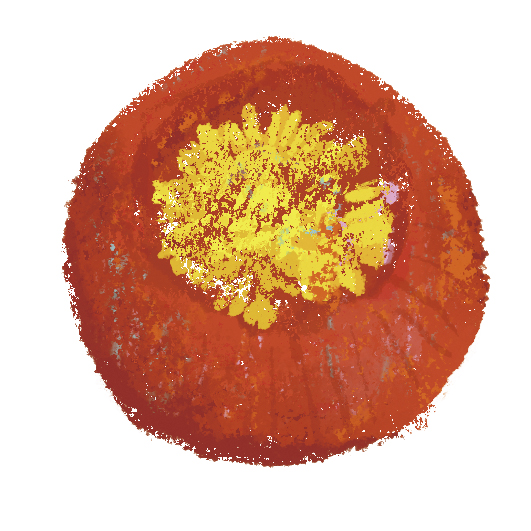

Kashigata, traditional hand carved wooden molds used in making wagashi, is the perfect embodiment of this spirit. Traditionally, kashigata must be made from wood from century-old mountain cherry trees. Carving motifs such as flowers and fish on hardwood blocks require expert hand engraving skills to achieve an intricate and vivid result. Now a fading art, only several kashigata artisans remain. Engraving involves carving inverted images. To capture the curves of a petal, artisans must feel its shape and space before carving the negative image. In the classic In Praise of Shadows, Japanese novelist Junichiro Tanizaki writes, “We find beauty not in the thing itself but in the patterns of shadows, the light and the darkness, that one thing against another creates”. Perhaps the pattern of light and darkness is the reason for kashigata’s acclaim in the art community around the world.

To the Japanese, humans coexist with nature. Living with four distinct seasons, the Japanese are keenly aware of the changes, their daily lives shifting to the ebbs and flows of the 24 solar terms. The naming of different wagashi reflects this: in winter, a pale white wagashi is named “Light Snow”; summertime sees “Green Plum” and “Waterfowl”; wagashi in spring celebrates the flowering of cherry blossoms; autumn reminisces on the changing colours of maple leaves. When everyday life follows the natural rhythm, people live in harmony with nature and find that everything in the world is intimately connected. The Japanese also hold artisans and their tools with the utmost regard. The most accomplished artisans are recognised as “Living National Treasures”. At the same time, many private museums collect these traditional tools and wares — the Kanazawa Museum of Wooden Japanese Sweet Molds is just one of many examples. Perhaps the Japanese philosophy of life can be summed up as the experience of time through things. In this way, we can accept imperfections in life and learn to pursue simplicity. After all, every moment is a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

You May Also Like...

This site uses cookies. Please indicate your consent. Learn more here.